The absurdity and calamity of US tariff policies

US tariffs are poorly designed, badly implemented and are already damaging both the US and global economies. The economic damage will only get worse as uncertainty further undermines business and consumer confidence and results in dislocation of global supply chains.

Determining the extent of economic damage, and financial market implications, is difficult because we don’t know what tariffs will actually be implemented or how many backflips there are before then. There’s no clear, defining strategy. The justification for tariffs oscillates between reinvigorating US manufacturing, raising revenue to fund tax cuts, the cost of the US providing global security, the provision of the US dollar to support global trade and financial markets, and broadly addressing an ‘unfair’ trading system. Different justifications would lead to different structures of the tariff regime. Adding to uncertainty, key individuals in the administration have different goals for tariffs.

1. The obsession with bilateral trade deficits is baseless

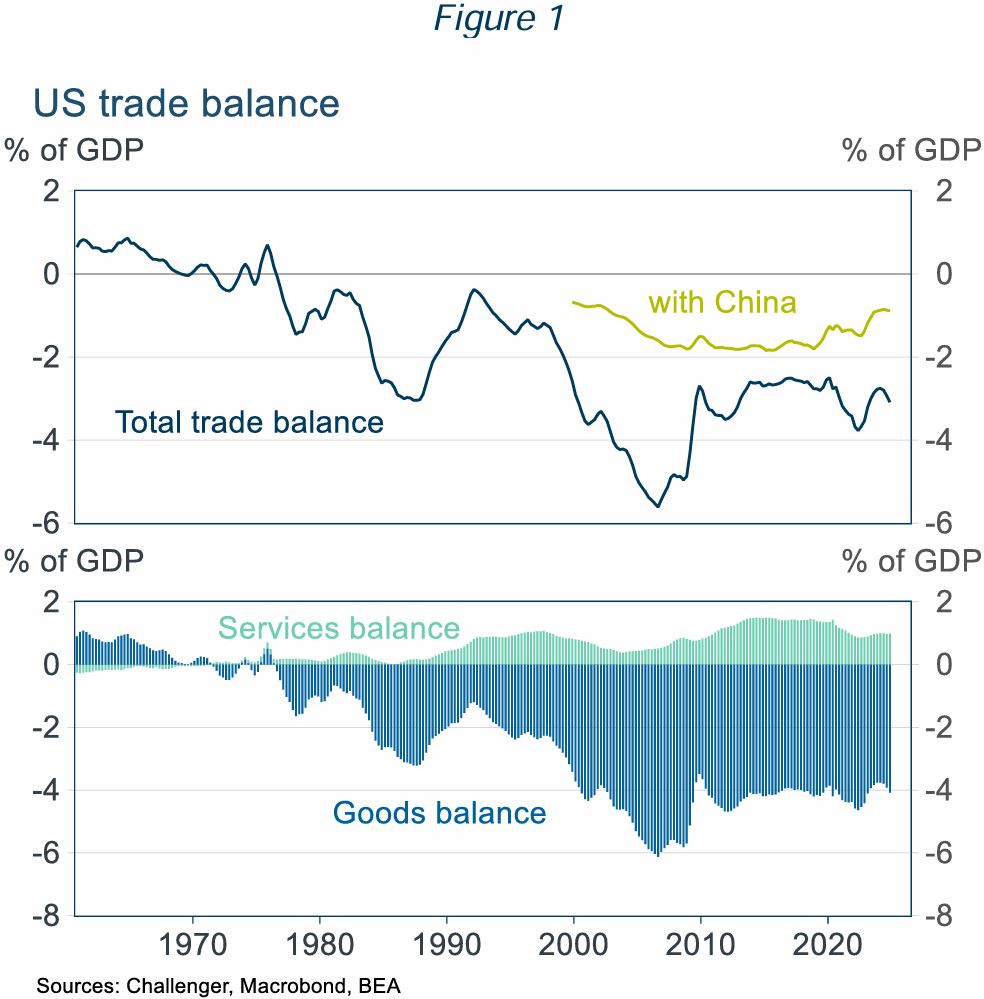

President Trump’s tariff obsession is rooted in a dislike of trade deficits. The United States has run a trade deficit since the mid-1970s (Figure 1). He attributes this deficit to unfair trade policies in other countries and an overvalued US dollar, resulting from US dollar demand given its role in international trade and finance. But the trade deficit also depends on US domestic conditions, notably the US Government’s huge fiscal deficit, currently 5% of GDP.

Balanced national trade doesn’t need bilateral balanced trade

Even if balanced trade at the country level was desirable, there is no reason for this to apply country by country. Even countries with balanced aggregate trade run large trade deficits or surpluses with almost all of their trading partners: Belgium had balanced trade with just two countries; and Canada, Finland, South Korea and South Africa each had balanced trade with just one of their trading partners. Each of these five countries had significant bilateral trade surpluses or deficits with over 150 of their trading partners. The US goal of balanced bilateral trade with every country is, frankly, bonkers.

2. The calculation of tariff rates is absurd

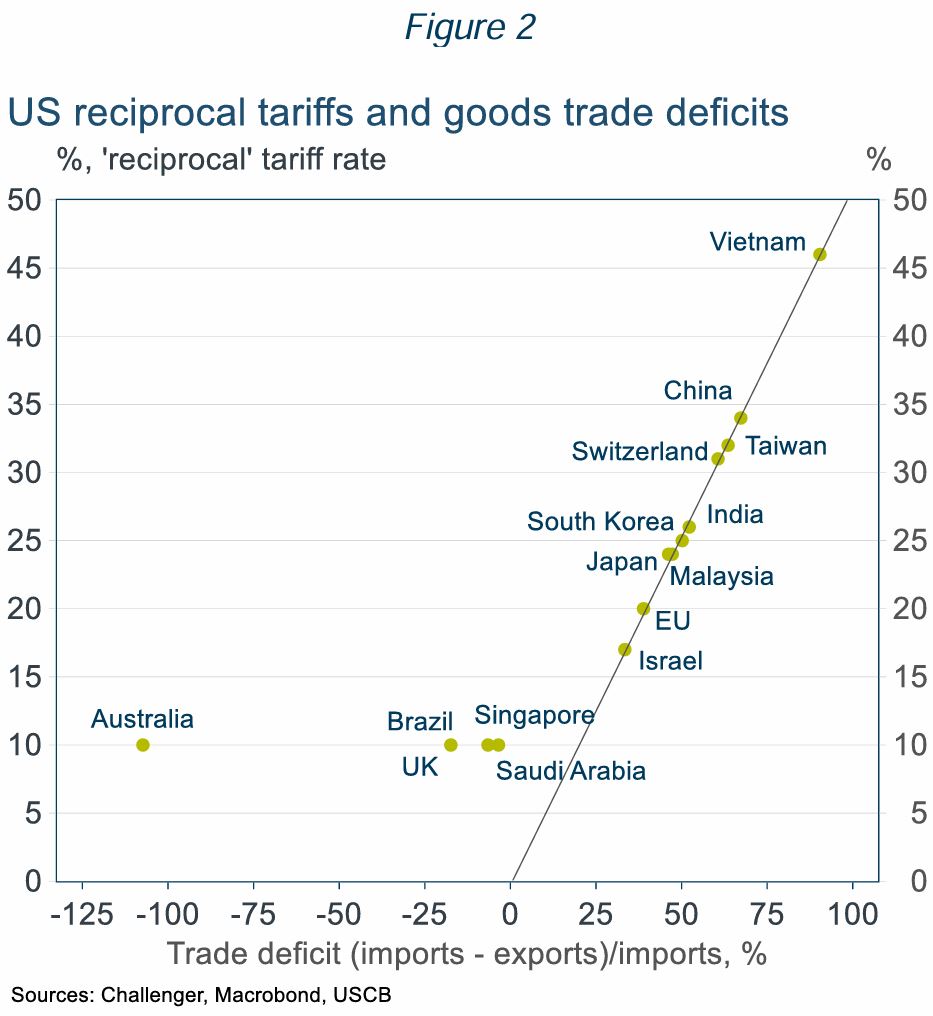

- Bilateral trade balances are meaningless but determine the US ‘reciprocal tariffs’ (Figure 2).

- Even countries the US has a trade surplus with, including Australia get a 10% tariff. If Australia applied the same logic as the US, we’d impose a tariff on the US of around 50%.

- The US has a surplus in services trade of 0.25% of GDP (partly offsetting the goods trade deficit of 1% of GDP; Figure 1) but ignores services trade in its calculation of tariffs.

3. The tariffs are badly designed reflecting unclear and inconsistent goals

The US tariff regime has a mix of tariffs on specific goods (steel, aluminium, vehicles) and on specific countries (Canada, Mexico, China and the reciprocal tariffs) reflecting the varied goals of the tariffs. But many of these goals are in conflict. If, as Trump claims, tariffs raise revenue without increasing US prices by forcing foreign suppliers to absorb the tariff, then US manufacturers won’t be more competitive as US prices won’t be higher. And if tariffs are successful in boosting US production, then there would be fewer imports, and so less tariff revenue.

Several bad design elements of the tariffs mean there will be further changes:

- Different tariff rates distort trade for little benefit – for example, Apple intends to ship iPhones to the US from India rather than China as US produced iPhones would be prohibitively expensive.

- High tariffs are being applied to goods the US can’t, or won’t, ever produce – for example, some minerals and shoes (most come from China and Vietnam with 145% and 46% tariffs).

- Tariffs are being applied to inputs used by US manufacturers, increasing exporters’ costs.

4. The effective trade embargo with China will be disruptive to the US economy

The 145% punitive tariff applied to China makes most imports from China prohibitively expensive. But the US economy is not ready to disengage from China, which has supplied 13% of US imports. Factories don’t pop up overnight.

Using a fine disaggregation, breaking down goods into their constituent parts, over half of US imports are from China. Alternative suppliers just don’t exist.

For finished consumer goods with very high import shares from China, large price increases and stock shortages will be disruptive to consumers and impact consumer sentiment and support for tariffs. The economic impact will be even greater for those imports predominantly sourced from China that are used as inputs in US production, such as explosives, machinery and various chemicals. For example, China is also a key source for base ingredients used in manufacturing medicines and finished medicines.

5. The tariff regime won’t survive its poor design, but tariffs won’t go away completely

The US tariff regime is already unravelling with holes poked in the tariff wall.

- Reciprocal tariffs were paused until 9 July (the baseline 10% tariff still applies to all countries).

- Consumer frustration will mount facing higher prices and product shortages. For example, phones, computers and some other electronics have been exempted from the China tariffs.

- Businesses are getting traction lobbying on the cost to production from tariffs, for example there will be a partial rebate on the 25% tariffs on car parts used as inputs in US manufacturing.

- The US has said some 70 countries want to negotiate tariff reductions. Yet negotiating a detailed trade agreement takes time. The renegotiation of the US-Canada-Mexico trade agreement in President Trump’s first term took 18 months. A rushed negotiation will contain flaws.

However, President Trump strongly believes in the benefits of tariffs for promoting US manufacturing and he needs the revenue. He has committed to using tariffs to reduce income taxes, even musing that income taxes could be eradicated. But a 10% uniform tariff has been estimated to raise just $1.7 trillion over 10 years, a 20% tariff $2.6 trillion. This is substantially less than the estimated cost of $5 to 11 trillion of the tax cuts already promised by President Trump.

6. What does the future hold?

There will be many more turns in the road with backflips, reduced tariffs for goods the US won’t produce or needs and new tariffs. There will be ‘deals’ reducing (but not eliminating) individual tariffs with countries committing to reduce trade barriers and import US goods (much of which will never happen).

The pause in reciprocal tariffs, after just one week, was reportedly triggered by the turmoil in bond markets which could have precipitated a financial crisis. Trump has displayed greater resolve in the face of the large fall in equity prices than in his first term. But the risk of a financial crisis, or severe recession, and sharp falls in approval ratings are likely to remain red lines that would result in some pullback.

Challenger expects ongoing tariff uncertainty and hence further volatility in markets. Aggregate tariffs will never get to the levels initially announced, but they will also be much higher than before, reducing US and global growth. Tariffs will add to US inflation, reducing the ability of the Fed to ease. Market pricing is for almost 100 basis points of cuts this year, but there’s a good chance the Fed does not even cut this year.

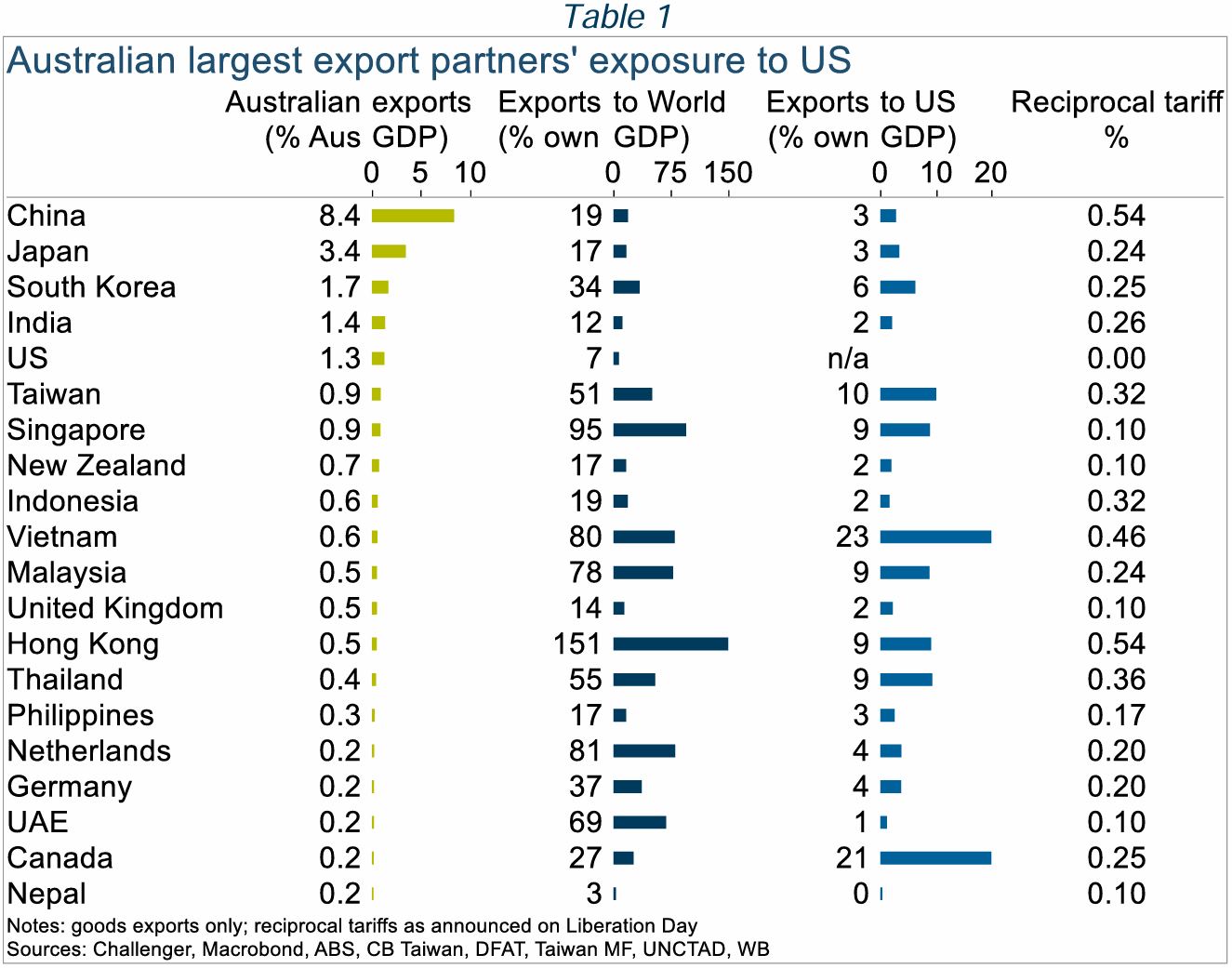

Australia will also see slower growth. We have limited direct exposure to the US economy, but our largest trading partners are more exposed (Table 1). The IMF downgraded its GDP growth forecasts for 2025 by 0.5%. Slower growth, and China’s surplus manufacturing capacity reducing Australian import prices, will lower inflation opening the path to RBA rate cuts. However, market pricing for a cash rate below 3% by December is overdone. With the worst case for US tariffs unlikely to play out, three cuts bringing the cash rate to 3.35%, around its neutral level, seems more likely.

Source: Challenger